First ever inter-agency global guidance on how to support kinship care

Submitted by Alena Sherman on Fri, 02/02/2024 - 12:39pmwritten by Family for Every Child

Across the world, around one in ten children are growing up in the care of their extended family. Depending on where they live, this could involve their relatives - both blood and through marriage - or close family friends. Often, although not always, referred to as kinship care, (kin meaning family) this type of care is increasing in many countries. Kinship care has benefits for both children and caregivers. Through it, caregivers find companionship, practical support and the satisfaction of helping a much loved child to flourish. Children who don’t live with their biological parents prefer it over other types of care. It offers the stability, continuity, sense of belonging and links to family identity that foster care or institutional care might lack.

Across the world, around one in ten children are growing up in the care of their extended family. Depending on where they live, this could involve their relatives - both blood and through marriage - or close family friends. Often, although not always, referred to as kinship care, (kin meaning family) this type of care is increasing in many countries. Kinship care has benefits for both children and caregivers. Through it, caregivers find companionship, practical support and the satisfaction of helping a much loved child to flourish. Children who don’t live with their biological parents prefer it over other types of care. It offers the stability, continuity, sense of belonging and links to family identity that foster care or institutional care might lack.

We are all rooted in our family in one way or another and the depth of these roots plays a large part in how we find our place in the world. The Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children recognises this when it states that kinship care should be the next choice for children outside the care of their biological parents. Surprisingly, although kinship care is widely used, recognised and valued in many countries, it is remarkably under-supported by governments. Whilst most children in kinship care are well loved and well cared for, lack of support can place them at risk.

So how can we reduce the risk?

One of the first steps is to explain why supporting kinship care is so important and why policy change is essential. Family for Every Child, a global alliance of local civil society organisations working with children, has done just that. In collaboration with other key stakeholders, Family for Every Child has facilitated the development of global guidance on kinship care. Aimed at both policymakers and practitioners, the guidance puts forward a clear and compelling argument for the support of kinship care. It also provides principles of good practice and lessons learnt from across the world.

The guidance highlights that the needs of kinship caregivers and children can be complex and responses can’t be simple. The needs of kinship caregivers differ from the needs of biological or foster and adoptive parents, and therefore support services need to tailor their services accordingly. They need to involve many different services and people, especially kinship caregivers and children. In some contexts, this might mean care systems need to become more family-focused and strengths-based. In others, the social workforce may need upskilling to better understand and respond to the needs of kinship care.

All kinship caregivers and the children in their care, no matter where they live, should have access to the support they need to keep them safe and help them flourish. The guidance is now available. Join us n spreading this message by downloading and sharing the guidance across your networks.

Using the INSPIRE Framework to Strengthen the Social Service Workforce in Uganda

Submitted by Alena Sherman on Thu, 11/30/2023 - 1:17pmSubmitted by Michael Byamukama Ntanda and John Mary Ssekate from the National Association of Social Workers of Uganda (NASWU)

INSPIRE is a global framework of seven mutually reinforcing strategies for preventing and responding to violence against children and adolescents. They include implementation and enforcement of laws, norms and values, safe environments, parent and caregiver support, income and economic strengthening, response and support services, and education and life skills.

The 2018 Violence Against Children (VAC) Survey indicates that nearly 35 per cent of children in Uganda have experienced multiple forms of violence. Thus, strengthening the social service workforce for child protection is a top priority of the National Association of Social Workers of Uganda (NASWU). For the past five years, NASWU have implemented the following interventions modeled after the INSPIRE framework to strengthen the workforce:

Training the Trainers

Recognizing that social service workers are the frontline workforce responding to and supporting children affected by violence, NASWU has trained and equipped its executive and management team with knowledge on the INSPIRE framework and its contextual application in social work practice settings. They have also trained senior social workers from various social work agencies on the framework to build the capacity of social work service organizations.

With initial support from the Children’s Rights and Violence Prevention Fund (CRVPF), NASWU has also trained 50 trainers from different social work agencies, academic institutions and government departments. As a result, INSPIRE strategies have been integrated in organizational strategic plans and across different communities in Uganda.

Continuous Professional Development of Early Career Professionals based on INSPIRE

NASWU is working with universities across Uganda to equip social work students and recent graduates on the seven INPIRE strategies. Between 2022 and 2023, a total of 519 students and recent graduates from five universities have benefited from this training. Training university students has been found to be highly beneficial, as they are respected in their communities and have the ability to positively influence their friends, families and communities on methods to protect children from violence

Discussions with early career professionals has provided a unique opportunity for our association to listen and compare different cultural practices, structures and values. For example majority of the youth trained confirmed that Ubuntu values based on the sense of community, love, compassion are foundations for child protection among many African families and communities, while negative cultural practices in many African communities like auctioning of girls among Jonglei state of South Sudan, female genital mutilation among the Sabins in Eastern Uganda, and concealing information by family members where a child has been violated continue to perpetuate violence against children. All the students trained have signed commitment to be community bystanders and ready to report cases of violence in their communities on 116 national toll-free lines.

Advocacy

Using online platforms, NASWU is integrating INSIPIRE approaches to share messages on protecting children against all forms of violence. Frontline social workers are also supported with tools like the Standardized Case Management Tool and the Uganda National Child Protection Policy 2020, both of which link to the INSPIRE tool. Since the outbreak of COVID-19, NASWU has organized 20 online webinars and two advocacy campaigns focused on child protection and targeting frontline social service workers. A total of 1045 frontline social service workers from social work agencies, government ministries and departments, as well as from the private sector, have participated in online webinars and advocacy campaigns to protect children from violence focusing on different child protection areas like protecting refugee children, children in alternative care, child labor, child trafficking, and child mental health and psychosocial support.

Mentorship

NASWU is also using the INSPIRE tool to mentor social workers in communities who want to start child protection community change projects, organizations focused on child protection, and those with interest in research. Up to 30 social workers from not only Uganda, but also South Sudan and Rwanda have been supported by NASWU over the last two years.

The INSPIRE tool presents a great opportunity for strengthening the social service workforce in Uganda in dealing with all forms of violence against children. NASWU experience using INSPIRE reveals better outcomes when the interventions are done in collaboration with community structures, and with affected children and their families so that the root causes of violence against children can effectively be addressed.

Strengthening the Social Service Workforce for Family-Based Care: Learning from Young People with Lived Experience of Care

Submitted by Alena Sherman on Wed, 11/22/2023 - 10:21amThe Global Social Service Workforce Alliance, Child Frontiers and Martin James Foundation are delighted to announce an innovative new project beginning this year. This multi-national, multi-year project will work to learn from and amplify the knowledge and expertise of young adults with lived experience of care, their families, and social workers serving vulnerable children worldwide to develop a range of new training and advocacy tools for the social service workforce.

This project comes at a crucial time in history as nations are growing in the recognition of the value of family for every child’s development and well-being. This has led many to adopt new laws and policies to prevent the separation of children from their families and ensure family-based alternative care options are available when necessary. To ensure the social service workforce worldwide is ready to meet the requirements set forth in these new laws and policies, this project looks to learn directly from young adults with lived experience of care. Our hope is their expertise, insight, and knowledge will strengthen, deepen, and sustain the motivation and competencies of the social service workforce.

While research indicates the central role family plays in the healthy development of every child, many countries throughout the world still rely primarily upon residential care to provide alternative care for children. Millions of children are, therefore, growing up in residential care or are currently at risk of being separated for long periods of time from their families and communities.

As the first line of response for many children and families at risk of separation, a well-developed and supported social service workforce plays an essential role in helping countries achieve lasting family-based care solutions. It is critical to ensure that these social workers, paraprofessionals and community volunteers are well-resourced, trained and equipped to ensure that children are not unnecessarily separated from their original family and returned to their families and supported when separation has occurred. Further, when children do require alternative care, it is critical that the social service workforce be equipped to ensure that every child receives high-quality, family-based care through kinship care, foster care, or adoption.

This project aims to enhance this workforce’s skill set by turning directly to young people with lived experience of care. Implemented in Brazil, India and Uganda, the project will begin by documenting the knowledge and perspective of those with care experience through videos, written testimonies and other creative media. Expertise gathered will inform a series of training and advocacy tools in each country. The training tools will aim to enhance the knowledge, resources and practices of social service workers as they are increasingly motivated by and skilled in prioritizing family strengthening and family-based alternative care. The advocacy tools will aim to raise awareness of the crucial role of social service workers in supporting governments to reform care systems and of the need to increase long-term investment in this essential workforce, covering not only adequate salaries and resources, but the resources required to build and incentivize continuous professional development and supervision.

“Incorporating the knowledge and experiences of care-experienced youth, family members, and practitioners is crucial in shifting policies and workforce practices away from a reliance on residential care, ” says Hugh Salmon, Director of the Global Social Service Workforce Alliance. “The perspectives of those with lived experience can guide the creation of more effective alternative care models centred on the needs and wishes of the child and on empowering families to provide good care for their children. This will enable a more responsive and empathetic approach to protecting children who might otherwise be at risk of losing the care of a family.”

“As we aim to be led by young adults with lived experience of care, we are really pleased to be collaborating with the Global Social Service Workforce Alliance and Child Frontiers. We celebrate the fundamental importance of social workers and the pivotal difference they make in the lives of children and families. When they have the best, evidence-informed tools and resources available, children and families greatly benefit,” said Ailsa Laxton, Director of Global Programmes at Martin James Foundation.

Stay tuned for more information as this two-year project unfolds.

A Future of Challenge, But Also Promise, Lies Ahead

Submitted by Alena Sherman on Wed, 10/25/2023 - 6:09pmby Hugh Salmon, Director, Global Social Service Workforce Alliance

Now that the Global Social Service Workforce Alliance has reached its 10th birthday, and we reflect on the progress made to strengthen the social service workforce at all levels, do we know what challenges lie ahead? And, are we ready to meet them?

Now that the Global Social Service Workforce Alliance has reached its 10th birthday, and we reflect on the progress made to strengthen the social service workforce at all levels, do we know what challenges lie ahead? And, are we ready to meet them?

In our first ten years as an alliance, we brought together a diverse, global membership, determined to bring global attention to the needs, and vital role of, a vast and unrecognised social service workforce. To do so, we worked with our members, partners, and supporters to develop a wide range of technical resources to help plan, develop and support the workforce across the globe. Our efforts, in partnership with various governments and UNICEF, to map and assess the social service workforce, revealed that the workforce is built around the core profession of social work, but to be effective and reach all those in need, it needs to unite a whole ecosystem of community volunteers, para professionals, supervisors, researchers, educators and policy makers, spanning public sector, private sector and civil society organisations, and those working in health, education and justice sectors, as well as in social welfare.

Once we had captured people’s attention at the 2010 Social Welfare Workforce Strengthening conference, and launched as an alliance in 2013, we have learned how the workforce has had to adapt and respond to a series of complex needs and emergencies: from the impact of HIV and AIDS to the impact of poverty, social, and racial injustice, to the impact of violence and lack of safe family-based care faced by millions of children worldwide. In early 2020, when COVID-19 started to spread rapidly, the workforce and its leaders were initially unprepared to cope with the impact of the pandemic on children, families and vulnerable individuals, but within a few months, and in some countries only a matter of days, the workforce rose to the challenge. They shifted to online ways of working and communicating, supervising and learning, while successfully lobbying to be recognised as an essential workforce that needs the protective equipment and the authority to continue visiting homes and communities, to deliver life-saving support, care and protection, and to dispel myths and restore hope.

Social service workers, leaders and planners are now waking up to an even greater set of challenges resulting from accelerating climate change. We used to think that these issues were for environmental scientists, governments and UN bodies to address. We were aware that we all had to rethink our ways of living and working, reduce our carbon footprint and stop destroying our natural world, but we did not realise that as social service workers we would be addressing the consequences of climate change in our daily work, from families losing their livelihoods and being forced to migrate, to wildfires, floods and droughts destroying homes and communities. We now realise that we have the power and responsibility to act: to help people understand the risks and the need to prepare and adapt, but also to help with recovery. In 2022, this realisation brought our alliance together with a unique global gathering of people and organisations, not only social service workers but health workers, students, trade unions, indigenous rights activists and faith-based organisations, inspired by the human connectedness of Ubuntu, in a global online summit where we signed the first People’s Charter calling for the co-building of an Eco-Social World.

Social service workers, leaders and planners are now waking up to an even greater set of challenges resulting from accelerating climate change. We used to think that these issues were for environmental scientists, governments and UN bodies to address. We were aware that we all had to rethink our ways of living and working, reduce our carbon footprint and stop destroying our natural world, but we did not realise that as social service workers we would be addressing the consequences of climate change in our daily work, from families losing their livelihoods and being forced to migrate, to wildfires, floods and droughts destroying homes and communities. We now realise that we have the power and responsibility to act: to help people understand the risks and the need to prepare and adapt, but also to help with recovery. In 2022, this realisation brought our alliance together with a unique global gathering of people and organisations, not only social service workers but health workers, students, trade unions, indigenous rights activists and faith-based organisations, inspired by the human connectedness of Ubuntu, in a global online summit where we signed the first People’s Charter calling for the co-building of an Eco-Social World.These climate challenges, and resulting social upheaval, are compounded by the widening range of human conflicts, which result not only in mass casualties and trauma, and people losing their homes and families, but also in a breakdown of trust across ethnic and religious divides. We are seeing rising hostility and mutual blame, spreading online far beyond the site of the conflicts, sowing the seeds of future wars. To address these challenges, we cannot wait for outside help. Social service workers are embedded in every community, so we must unite our voices and efforts, not only to provide disability inclusive social care, child protection and mental health services, but also as local bridge builders, change agents and peacemakers. We need to be ready to support and protect when losses occur, but also committed to build empathy, mutual understanding and trust across communal divides, restore faith in humanity, and turn despair into hope, and a collective vision for a better world and a future of promise.

Equipping the Social Service Workforce to Meet the Needs of Children with Disabilities

Submitted by Alena Sherman on Wed, 10/25/2023 - 2:51pmby Lucy Marie Richardson*

Compared to their peers without disabilities, children with disabilities are more than twice as likely as to experience violence, are 32 per cent more likely to experience severe physical punishment at home, and are overrepresented in institutional care. They also face barriers to fully accessing and benefiting from child protection services. These barriers may be tangible, such as buildings without ramps or videos without captions, or they may be related to attitudes, beliefs, and unconscious bias.

UNICEF and the Global Social Service Workforce Alliance (the Alliance) recognize that a well-planned, trained and supported social service workforce is essential to ensuring that every child is protected from violence, exploitation, abuse, neglect and harmful practices. Therefore, to address these barriers, meet the needs of children with disabilities, and uphold their rights, the social service workforce must be equipped with the necessary knowledge and skills that will enable them to deliver their child protection functions in an inclusive and equitable manner – such as knowing what disability discrimination is and being able to communicate in a disability-sensitive way.

With this in mind, UNICEF has developed a new practical tool to empower the social service workforce to deliver their child protection functions in a disability inclusive way. The Disability Inclusive Child Protection Competency Framework for the Social Service Workforce builds on the “Guidelines to Strengthen the Social Service Workforce for Child Protection”, developed by UNICEF and the Alliance and on UNICEF’s broader work in supporting governments to strengthen the social service workforce and build inclusive and effective child protection systems. It is a practical and action-oriented tool centred around a comprehensive examination of functional social service workforce competencies and actions for disability inclusion. The tool can be used in a variety of manners, such as creating training workshops, mapping the social service workforce, developing inclusive child protection policies, and creating disability-informed child protection job descriptions. The full spectrum of the social service workforce for child protection can use and benefit from this resource. This includes those working in diverse contexts, ranging from humanitarian situations, to both low-resource and high-income countries. It also includes those working with different groups of children such as those in alternative care, displaced children, and children experiencing violence.

“I wish I had had this resource 20 years ago when I first started working in UNICEF, trying to get children with disabilities out of institutions, and providing services at community centres… we could only find medical information, we couldn’t find anything on how to support the social service workers.”

- Kirsten di Martino, Senior Adviser, Child Protection, UNICEF

This critical new tool will be exclusively launched during a webinar cohosted with the Alliance on 7 November 2023. Webinar participants will be the first to see an overview of the tool and how it can be used in practice:

REGISTER TODAY

* Lucy is a disability inclusive child protection expert, previous staff member and current consultant with UNICEF Headquarters. She is the lead author of the DICP Competency Framework.

Malaysia's "Heroes Among Us" Campaign Drives Support for Social Workers

Submitted by Alena Sherman on Mon, 10/23/2023 - 11:48amby UNICEF Malaysia

In Malaysia, social workers play a crucial role in addressing the diverse and complex needs of its population. With 18,750 reported cases of child abuse, neglect, abandonment and over 13,500 reported cases of domestic violence between 2020-2022, the need for qualified social workers is enormous. Their knowledge and skills help people in Malaysia overcome personal, social, and systemic challenges to live better lives. Without their contribution, it would be difficult to achieve the Malaysian targets of the Sustainable Development Goals.

While the job of a social worker is complex and challenging, social work is not regulated nor recognized as a profession by law in Malaysia. By comparison, it is regulated in neighbouring countries including the Philippines (1965), Singapore (2009), Thailand (2013), and Indonesia (2019). In addition, social workers face limited public understanding of their role and value, which include viewing social workers as charity or volunteer workers. This impacts demand for services and investment in social work. Finally, there are not enough social workers in Malaysia: only 1 for every 8,576 people compared to the ratios in the US (1:490), Australia (1:1,040), UK (1:3,025) or Singapore (1:3,448).¹

To promote social work in Malaysia, UNICEF Malaysia and the Malaysian Association of Social Workers (MASW) launched the "Heroes Among Us" Campaign on August 24, 2023 during the country's National Social Work Summit. The campaign was launched with three distinct components after months of planning involving a multi-stakeholder coalition: social media activation to increase awareness of social work among voters and the public; media engagement to mainstream stories about social work; and political lobbying to mobilise decision-makers and parliamentarians around the need for the Social Work Professional Bill. The Social Work Professional Bill has been pending since 2010, and re-newed attention on its benefits and needs is required.

Through this campaign, MASW and UNICEF’s mission is to raise awareness of the critical role that social workers play in the lives of children, families and communities in Malaysia and to ensure that every child and vulnerable person has timely access to qualified and competent social workers, when required.

Learn more about this important campaign.

Watch the Campaign Video:

¹ Malaysian Administrative Modernisation and Management Planning Unit (MAMPU), 2019

Envisioning the Future of Social Service Workforce Planning: A Data-Driven Approach

Submitted by Alena Sherman on Mon, 10/23/2023 - 11:19amby Alex Collins, Senior Technical Advisor, Data for Impact (D4I) project, Palladium

A robust social service workforce with the right number and types of social workers and social-service personnel, along with the required competencies and support, is central to the well-being of children, families, persons with disabilities, and other groups who face adversity. To identify promising approaches to strengthen the social service workforce and broader systems related to child care and protection, the USAID-funded Data for Impact (D4I) project has assessed key related activities across three countries—Armenia, Cambodia, and Rwanda.

A robust social service workforce with the right number and types of social workers and social-service personnel, along with the required competencies and support, is central to the well-being of children, families, persons with disabilities, and other groups who face adversity. To identify promising approaches to strengthen the social service workforce and broader systems related to child care and protection, the USAID-funded Data for Impact (D4I) project has assessed key related activities across three countries—Armenia, Cambodia, and Rwanda.

Findings reveal the advantages and challenges in different approaches to plan, develop, and support the workforce. Across the three countries, new positions were established to bring the workforce and services closer to children and families. These roles included community social workers in Armenia, child protection and welfare officers plus Inshuti z’Umuryango (translated as Friends of the Family volunteers) in Rwanda, and provincial to community level social workers and focal points in Cambodia. Improving the numbers and distribution of social service workers or volunteers at lower levels and strengthening their capacity has bolstered the ability of workers to reach those in need.

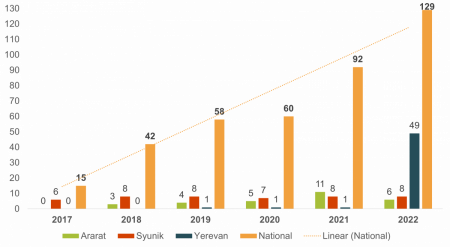

A Closer Look at Armenia: Legislating the Minimum Number of Community Social Workers

The Government of Armenia implemented a successful strategy of setting a minimum required number of community social workers. This was coupled with sustained, local financing of these positions. The Law on Local Self-Governance adopted in 2002, and subsequent amendments, established a requirement of 1 community social worker per 5,000 population, which previously was closer to one community social worker per one million total population. From 2017 to 2021, 91 community social workers were recruited and trained in 86 communitie. They were incorporated into staff lists, and funded by communal budgets. As of 2023, the total number of community social workers has risen to 129, reaching the target of one community social worker per 5,000 children nationally.

The Government of Armenia implemented a successful strategy of setting a minimum required number of community social workers. This was coupled with sustained, local financing of these positions. The Law on Local Self-Governance adopted in 2002, and subsequent amendments, established a requirement of 1 community social worker per 5,000 population, which previously was closer to one community social worker per one million total population. From 2017 to 2021, 91 community social workers were recruited and trained in 86 communitie. They were incorporated into staff lists, and funded by communal budgets. As of 2023, the total number of community social workers has risen to 129, reaching the target of one community social worker per 5,000 children nationally.

As described by a key informant, “When the program started, there were only eight community social workers in the regions and one social worker in Yerevan. Now the number has reached [129]. If we ask the question of whether this number of social workers is enough for a country with so many social problems, the answer is no. But comparatively, this number is huge from the perspective of the importance and effectiveness of having social workers in the communities.”

The Future of Social Service Workforce Planning Must Incorporate Demographic Data

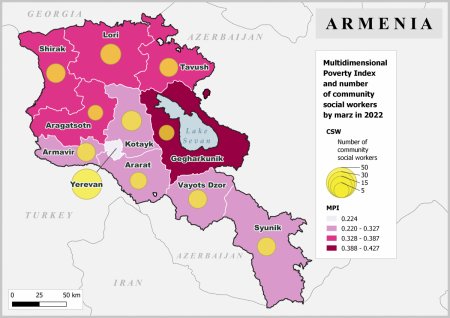

While significant progress was made to increase the number of frontline workers, there is limited use of human resources and demographic data to inform workforce planning. An analysis of the community social workers and their current geographic distribution in Armenia, compared with publicly available multi-dimensional poverty index (MPI) data, shows how current recruitment and deployment practices have yet to incorporate this information.

While significant progress was made to increase the number of frontline workers, there is limited use of human resources and demographic data to inform workforce planning. An analysis of the community social workers and their current geographic distribution in Armenia, compared with publicly available multi-dimensional poverty index (MPI) data, shows how current recruitment and deployment practices have yet to incorporate this information.

As shown in the map to the right, the highest number of community social workers are concentrated in Yerevan, while fewer are posted in areas classified as low- to mid-range on the MPI, and the lowest number is in Gegharkunik, which is at the higher end of the poverty index. A key informant from a local educational institution stated, “We have a serious shortage and uneven distribution of personnel in the regions. We have an accumulated labor force in Yerevan, and we have a problem of finding specialists in the marzes.”

In areas where community social workers are scarce, they can find themselves serving communities of 10,000 or more, negatively impacting the quality of services provided. One expert interviewed for the assessment states that in such districts, “high workload for community social workers…is a problem. Community social workers besides their professional duties, as community workers, carry out other duties as well.” Some Armenian communities have advocated for the integration of a second community social worker position in each community, to address workloads and align with the latest legislation. Similar efforts to increase the number of frontline workers were also reported in Cambodia and Rwanda, but these were based on calculations of workload and workforce-to-population ratios, not the different level of needs in communities.

Governments and implementing partners need to consider how to make a case for investing in the social service workforce by collecting and using demographic data and information on local community needs. The Alliance and its members should consider this question as we envision a future of promise in strengthening the social service workforce.

Stay tuned for an upcoming webinar and the release of global and country-specific reports, which will further present findings from D4I’s assessment of investments in the social service workforce. Click here to recieve email updates to stay informed about their release.

The Power and Potential of Social Work in South Africa

Submitted by Alena Sherman on Wed, 10/18/2023 - 5:13pm Twenty-seven years into its celebrated non-racial democracy, South Africa is in the unenviable position of being among the most unequal in the world, with exceptionally high rates of poverty and unemployment. The country is beset with a range of challenges, including high rates of corruption and crime, gender-based violence, femicide, child abuse, high carbon emissions and the consequences of climate change. The history of colonialism and apartheid have enduring effects on South Africa’s development trajectory, compounded by the neoliberal choices made by the post-apartheid government.

Twenty-seven years into its celebrated non-racial democracy, South Africa is in the unenviable position of being among the most unequal in the world, with exceptionally high rates of poverty and unemployment. The country is beset with a range of challenges, including high rates of corruption and crime, gender-based violence, femicide, child abuse, high carbon emissions and the consequences of climate change. The history of colonialism and apartheid have enduring effects on South Africa’s development trajectory, compounded by the neoliberal choices made by the post-apartheid government.

Unemployment is a major source of poverty and inequality in South Africa. Unemployment among youth is a shocking 66.5 per cent under the official definition, which is a recipe for instability, chaos and disaster. Being gainfully employed is central to one’s sense of identity and purpose; the absence of which can contribute to feelings of unworthiness and nihilism, which underlie much of the social ills that social workers deal with. Black women share a high burden of unemployment of over 38 per cent. The top 10 per cent wealth group is composed of 60 per cent White South Africans, who represent less than 10 per cent of the total population. The legacy of apartheid endures with race and gender being powerful determinants of access to resources.

Under circumstances of extreme poverty and inequality, it is easy to manipulate identities and incite people into violence. South Africa bore witness to this in July 2021 when, over eight days, thousands of people took to the streets, looting and burning stores and shopping malls, particularly in the provinces of Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal (KZN), with KZN bearing the brunt of the mayhem. The death toll was 342 – the worst in South Africa’s post-apartheid history – and the estimated cost to the South African economy was R50 billion (about US$3.4 billion). Widely reported on national and international television, the anarchy we witnessed was surreal, as people unrelentingly, throughout the day and night, engaged in the looting and arson, making places look like war zones, often in full view of the police. While the poor must not be demonized and held responsible for the chaos, as one person on the Social Work Action Network, South Africa (SWAN, SA) on 13 July 2021 wrote, “But if you’re a disaffected, unemployed, struggling youth with a lot of anger at the total lack of anything your life seems to offer under this unequal system, expressing that anger and looting some stuff becomes pretty appealing.”

Against this deep abyss, engaged citizens and social activists, including social workers continue to provide a politics of resistance and a politics of hope, as they try to hold government accountable.

Even with the odds stacked against them, and the fact that the welfare sector struggles with challenges of lack of funding, high staff turnover, poor salaries, poor working conditions, heavy workloads and staff burnout, social workers provide promotive, protective and preventive services in generic and various specialized fields. Social workers unassumingly and without fanfare, quietly go about fulfilling their responsibilities with the most marginalized, oppressed and vulnerable groups of society, and through a multiplicity of roles contribute to the Sustainable Development Goals. Although they are frontline human rights workers, they are often not recognized as such both within and outside of the profession.

The Minister of Social Development, Lindiwe Zulu, in March 2021, expressed concern about the shortage of social workers and the high number of unemployed graduates, in light of the prevailing socio-economic challenges and social ills confronting our country. COVID-19 saw the recruitment of more social workers into the workforce. In order to implement the Presidential 5-Point Plan and the National Strategic Plan on Gender-Based Violence and Femicide that was launched on 30 April 2020, the Department of Social Development employed an additional 200 permanent social workers to focus specifically on gender-based violence, while a number were employed on contract to respond to psychosocial issues linked to Covid-19. In his address to the nation on 30 March 2020, at the height of the pandemic, President Cyril Ramaphosa acknowledged social workers, as one among other groups of persons, who “keep the country going in these difficult times”

The private hospital group, Netcare, appointed 61 social workers across 33 Netcare hospitals in 2021. Netcare noted that because of the integration of social workers, "The patients and their families were very appreciative of the services provided…[and the] supportive services available to [staff members] in their immediate working environment made a huge difference to their emotional wellbeing."

On 16 August 2023, Dr. Velo Govender hosted a dazzling denim and diamonds breakfast to honour social workers. Drawing on the results of her PhD, Dr. Govender addressed the impacts of neoliberalism and new public management on child welfare services. The event was attended by 120 social workers, and it was heartwarming to see former students in leadership positions, holding the torch and working in the interests of individuals, families and communities.

Present at the event was the Minister of Social Development, Lindiwe Zulu, who lavished praise on social workers, elucidated their many fields of practice, and pointed out that whenever there are disasters, social workers are often first on the scene, contending with very difficult circumstances. She talked about the need to have far more social workers in the country and acceded that, while government appreciated their services, social workers were not acknowledged enough. Those of us present at the event talked about the way forward and set up a task group that would develop strategies to engage in collective joint action. We hope to hold government accountable to the promises made, the laudable expressions of the Minister, and to challenge government to work towards adopting genuine people-centred, emancipatory approaches and towards greater equity between the public social services sector and non-governmental organizations.

Given the unique positioning of social workers as they promote social change and development, social cohesion and the empowerment and liberation of people by engaging people and structures to address life challenges and enhance wellbeing, social work - more than any other profession - holds the potential to bridge the gap between politics as lived out at the micro level and macro level. The rich value base and ethical principles of the profession, combined with the knowledge and skills that social workers possess, mean that social work has the potential to be politics with soul and to truly make a difference.

Breaking the Silence: Weekly Campaigns Shaping Mental Health Awareness in Nepal

Submitted by Alena Sherman on Mon, 10/16/2023 - 10:24pmby Aishworya Shrestha, Deputy Chairperson at Antardhoni Nepal

In the bustling streets and public squares of Nepal, a small group of social service workers gathers every Saturday. Armed not with banners or slogans, but with knowledge and empathy, they are on a mission to break the stigma surrounding mental health. These weekly awareness campaigns are transforming perceptions and fostering a more inclusive dialogue about mental well-being.

In the bustling streets and public squares of Nepal, a small group of social service workers gathers every Saturday. Armed not with banners or slogans, but with knowledge and empathy, they are on a mission to break the stigma surrounding mental health. These weekly awareness campaigns are transforming perceptions and fostering a more inclusive dialogue about mental well-being.

Nepal, like many countries, grapples with a deep-rooted stigma surrounding mental health. Conversations about emotional well-being are often hushed, and individuals experiencing mental health challenges are met with silence and misunderstanding. This stigma is particularly pronounced among older generations, where seeking help for mental health concerns is seen as a sign of weakness.

Every Saturday, our team from Antardhoni Nepal takes our awareness campaign to public places, becoming a beacon of hope and knowledge. Our mission is clear: to break the silence and dispel the myths surrounding mental health.

Curiosity Meets Stigma

As people bustle through the public spaces, curiosity often gets the better of them. They approach the campaigners, eager to know more about the cause we are championing. However, a curious pattern has emerged—when people discover that the topic is mental health, many quickly claim that they are 'fine' and that they have “no mental health”.

As people bustle through the public spaces, curiosity often gets the better of them. They approach the campaigners, eager to know more about the cause we are championing. However, a curious pattern has emerged—when people discover that the topic is mental health, many quickly claim that they are 'fine' and that they have “no mental health”.

This reaction is especially common among older generations, who have grown up in a culture of silence around mental health. The stigma runs so deep that acknowledging any form of mental health struggle is often seen as taboo.

A Shift in Perception

While the response from older generations is marked by hesitation and denial, the campaigners have observed something different among the younger crowd. Young people seem more aware and open to discussing mental health. They are willing to engage in conversations and ask questions, signaling a shift in perceptions.

Fostering Dialogue

We know that changing deep-seated stigmas will take time and patience. We do not expect to erase the stigma in a single campaign, but we believe in the power of dialogue. Each Saturday, we engage in conversations, answer questions, and share stories of hope and recovery.

A Path to Progress

The weekly awareness campaigns are just one step on the path to progress. They are a testament to the resilience of those committed to breaking the silence surrounding mental health. While the journey is ongoing, these campaigns have ignited a spark of change—a spark that has the potential to grow into a beacon of hope for a more inclusive and compassionate society.

As we witness these efforts unfold, we are reminded that the journey toward better mental health is a shared one. It's a journey where every conversation matters, every mind enlightened is a victory, and every heart touched brings us closer to a world where mental health is a topic not shrouded in darkness, but openly discussed, understood, and supported.

Antardhoni is a women-led organisation working for a more aware, accessible and affordable mental health services in Nepal.

Putting Together Puzzle Pieces

Submitted by Alena Sherman on Mon, 10/16/2023 - 4:00pmby Maury Mendenhall, Senior Advisor on Orphans and Vulnerable Children, United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Office of HIV/AIDS.

I am a social worker by training. But for most of my career, I never thought I could consider myself one.

I am a social worker by training. But for most of my career, I never thought I could consider myself one.

Since graduating with my Masters of Social Work, I have worked at the international level. With each role, I developed a stronger understanding of the difficulties faced by children and families under varying circumstances. I observed brilliant ways children and families were able to work together with relatives, friends, communities, and religious and government resources—as well as ways that the individuals themselves overcame challenges and supported others to do the same. But each job seemed to push me further and further away from opportunities to work with the people I always imagined I would support directly.

After I arrived at USAID, my wonderful supervisor, Gretchen Bachman, told me that my social worker background was one of the reasons I was hired. Gretchen not only valued social workers, but she wanted me to find ways to build and strengthen social service workers across multiple levels of our programming in global health.

She had a beautiful vision for social service workers and their critical role in efforts to address social determinants of health (SDH). The World Health Organization (WHO) refers to SDH as non-medical factors that influence health outcomes. It is only by understanding and influencing the forces and systems shaping the conditions of people’s daily lives that we can influence and improve health. The 2022 report, “Social Service Workers in Health Facilities,” covers this in more detail.

A few months into my first year at USAID, Gretchen encouraged me to work with partners to organize a conference on social service work, which was held in Cape Town, South Africa in 2010 and supported by the U.S. Government through the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). I will always consider this conference life changing.

It was a conference full of “aha” moments. I had trained to be a social worker because I love children and families. But during the conference, I was also reminded that I really love social service workers.

The conference provided us a wonderful opportunity to share experiences, ideas, successes, and challenges and celebrate workers that are so often underappreciated and overlooked. I know that this conference sparked “aha” moments for others too, because we were so eager to keep talking, collaborating, and growing a larger and stronger global network with a team of social service workers. We didn’t want the conference to end.

When the Global Social Service Workforce Alliance was officially born in 2013, I finally felt like a real social service worker. Social service workers operating at the micro and meso level with families and communities are fundamental. But there is also a role for me, supporting efforts to pull everything together at the macro level.

My team at PEPFAR was the primary funder of the Global Social Service Workforce Alliance for the first four years of its infancy. It is exciting to see what our colleagues from PEPFAR countries who attended the conference—and are now active members of the Global Social Service Workforce Alliance—have achieved over the past 13 years. It is also exciting to see what the Alliance has grown into, and to realize that it has become so much more than what was first conceived at the Cape Town conference in 2010.

Social service workers put together all of the puzzle pieces that are the most difficult to find. We cannot end the HIV epidemic by 2030 without their help. I am so proud to be a social service worker. There is nothing I would rather do than help social service workers solve puzzles, earn the respect and support they need to do this important work, and know that they should be so very proud of their roles as social service workers too.