My name is Nyarueni

Submitted by Alena Sherman on Tue, 10/26/2021 - 12:52pmBy Glynis Clacherty, lead researcher on the Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action's Community Engagement in Case Management project.

"My name is Nyarueni; I am 43 years old. When I was a child, I used to dream that one day I [would] become an educated and independent woman who would work for a brighter future for all women and girls in my community. I used to think that every dream of mine was reachable, until I experienced the chaos of the civil war back in my country, South Sudan.

I never imagined I would end up this way—being uneducated and all my dreams destroyed by things which were out of my control. I lost my hope and I gave up on my dream. It was all gone as a blink of an eye. I was forced to get married when I was only 17 years old, but I wasn’t angry with the decision of my parents because I had already lost my hope and at that time, “surviving” was all I was thinking about.

After a few years, I came to this refugee camp in Ethiopia. I looked at the situation of the children here, and I decided to step forward. I wished for them to live in a protected environment so that they can dream big and become successful and not lose their hope like I did. I have been working voluntarily as a child protection committee chairperson for the past three and [a] half years. I serve the children now. I facilitate meetings with the committee and develop action plans about what to accomplish in a certain time period. I conduct awareness raising and mobilization activities within communities about child protection concerns, [and the] available services to children with protection risks and child rights. I also do home visits and assist caseworkers in identifying children with protection risks, exploring alternative childcare options, and tracing parents or relatives of children.

I sometimes come to the child friendly spaces and tell resilience building stories to the children. I am proud that I am now giving children a chance to see a brighter future. It is never too late.”

Community volunteers, such as Nyarueni, are an integral part of preventing and responding to cases of violence, abuse, neglect and exploitation of children in humanitarian settings. They have a deep understanding of their communities, and help to identify children who are at-risk, have experienced harm, or have been separated from their family.

Nyarueni shared her story, along with other child protection volunteers from all over the world, as part of a project, led by the Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action, focused on promoting evidence-based best practices for the use of community volunteers in child protection case management in humanitarian settings.

Working on the project, our team has been overcome with a mix of admiration and awe for these volunteers. We feel proud to be colleagues with people who offer their hearts and minds, and often their money, to help children in their communities. We have learned how volunteers—who may not be highly educated—are able to incorporate child protection practices into contexts where social norms and the nature of humanitarian emergencies work directly against them. We have seen how volunteers are a bridge to services for children and their families.

Alongside this pride, though, we have also felt sadness. While volunteers experience many positives from their work, they also experience risks. Our research has showed that many projects engage community volunteers without carefully thinking through their roles and responsibilities.

We have heard stories of volunteers expected to work long hours, leaving no time for them to earn an income for their families, and of volunteers unable to sleep because they were worrying about handling high-risk cases without the support of experienced caseworkers. We also heard stories of volunteers being threatened by community members who assumed they were to be given certain items, such as food, from the volunteer because the role of the volunteers had not been properly communicated to the community.

The contrast between the commitment of our volunteer colleagues and the reality of what they often experience, has turned us into fierce advocates for the ethical engagement of volunteers. Our hope is that the key resources we have developed through the project—including advocacy materials for child protection organizations, governments, donors and policy makers, and guidance, tools and trainings for program designers and managers—will support this change.

Please visit the Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action website to access all resources associated with this project (including a study report and brief, a policy brief and a poster highlighting seven best practices for volunteer engagement). A toolkit, which includes guidance on ethically engaging community volunteers, as well as a manual for training volunteers in low-resource humanitarian settings, will also be available next year.

The Role of Social Service Workers in Disaster Preparedness

Submitted by Alena Sherman on Mon, 10/25/2021 - 12:33pmA Q&A with Heather Boetto, Senior Lecturer in Social Work at Charles Sturt University

Heather Boetto is a Senior Lecturer in Social Work at Charles Sturt University and has also worked in the human services sector as a practitioner for over 10 years in various fields, including disability, child and family welfare, and school social work. Her research focuses on environmental social work, also known as ‘ecosocial work’ and ‘green social work’. She was awarded the University Medal in 2017 for her PhD, which culminated in the development of a ‘transformative ecosocial work model’ for practice. The Alliance recently spoke with Heather about her research focused on social work and disaster preparedness.

Heather Boetto is a Senior Lecturer in Social Work at Charles Sturt University and has also worked in the human services sector as a practitioner for over 10 years in various fields, including disability, child and family welfare, and school social work. Her research focuses on environmental social work, also known as ‘ecosocial work’ and ‘green social work’. She was awarded the University Medal in 2017 for her PhD, which culminated in the development of a ‘transformative ecosocial work model’ for practice. The Alliance recently spoke with Heather about her research focused on social work and disaster preparedness.

Question: Please tell us a bit about your background and the research you have done on social work and disaster preparedness.

I developed a love of nature as young farm girl growing up in regional Australia. I relished the freedom of climbing trees, caring for animals and experimenting with plants and bugs. My parents cared for the land and stock on our farm as a matter of importance and they valued the results of their labours. Not to romanticise my childhood though, I also experienced drought, floods, bushfires, and storms. I observed my family’s sheep suffer during times of drought and I experienced the panic of bushfire. These experiences added to the awe and respect that I developed for the natural environment.

My childhood experience was the basis for my career in social work. As a practitioner, I was particularly sensitive to the impacts of climate on human wellbeing. I found a like-minded social worker when I entered academia, and she nurtured my interest and encouraged me to focus on environmental social work (or ‘ecoSocial work’) – which was a bit marginal in those days. I still have a long way to go, but I’ve been learning about the importance of integrating disaster practice into social work. I’m partial to participatory types of research, and so I’ve been collaborating with practitioners, community service organisations and local emergency services to explore disaster preparedness and more broadly, an environmental approach to practice.

Question: While it is known that social workers play a key role in disaster response, your research brings to light that social workers should also play a key role in disaster preparedness. Why do you think it is important that social workers have a role in disaster preparedness?

While disasters are not new phenomena, we’ve had a real onslaught of disaster events worldwide of late. All of us have been impacted in some way, shape or form, whether directly or indirectly. The reason why disaster preparedness is so important is because the level of resilience in a community or group determines the level of impact that a disaster event will have. We know that marginalised groups find it more difficult to prepare for a disaster event, to respond to a disaster event, and to recover from a disaster event, and so developing disaster preparedness addresses issues of social and environmental injustice.

Question: Please elaborate on what role social workers may already play in disaster preparedness as well as what roles they may need to take on in the future?

To be honest, we need to do much more! The role social workers play in disaster preparedness is seriously lacking…but we’re getting better. Our role is to develop disaster preparedness and resilience in all aspects of our practice – within our organisations, with our staff and volunteers, with service users, and our local communities. We also need to advocate for the role that social workers play in climate issues. Preparing and responding to disasters alone isn’t going to resolve the underlying problems associated with human activities that cause climate change and subsequent increases in disaster events.

Question: How can we ensure that social workers are prepared/trained to take on such roles?

I believe all social workers should receive training in disaster practice as a core part of professional education – and not just in trauma counselling. Most people identify with the response and recovery phases of disasters, and yet, the level to which a community or group is prepared for disaster events indicates their capacity to respond and recover. Given the inequitable impact of disasters on marginalised groups, preparedness is intrinsically linked to social and environmental justice outcomes.

Question: What contextual factors might limit a social worker’s ability to effectively engage in disaster practice and how can they mitigate such factors?

The most common barriers practitioners talk to me about are around organisational issues. In Australia, many practitioners are employed by organisations where disaster practice is not seen as core business. Short-term funding contracts usually define daily activities and restrict practitioners’ capacity for holistic, multidimensional approaches to practice. Of course, this system is underpinned by neoliberalism, which is also at the heart of the global environmental climate crisis. This is not a coincidence!

How can we address barriers to disaster practice? Social workers (and all social service workers!) are the most creative, skilled, and energizing people I know. I’ve worked with practitioners to integrate environmental approaches into practice, and their advice is to – start small, be creative, and when possible, be bold!

Recognizing the Key Role of Social Service Workers in Emergency Preparedness and Response

Submitted by Alena Sherman on Fri, 10/22/2021 - 10:18amBy Hugh Salmon, Director of the Global Social Service Workforce Alliance

Escalating conflicts leading to internal displacement and migration, the increasing frequency and intensity of climate-related disasters and a global pandemic have led to rapid increases in the numbers of people and communities in need of emergency social assistance and social work support over the past few years. These crises have compounded existing problems of persistent poverty, socio-economic inequality and social injustice, and have disproportionately impacted women and children.

Social service workers play a crucial, but often unrecognized role, in helping people and communities prepare, adapt and respond to such emergencies and crises. Social service workers have the skills, knowledge and commitment to identify, reach, assess and engage with the most marginalized members of society. These include not only those facing social, economic or health disadvantages, but also those experiencing or fleeing ethnic or racial discrimination and oppression, homelessness, war or civil conflict, natural disasters or the effects of climate change.

To address these challenges, the social service workers are well placed and equipped to assess needs and coordinate the necessary services from different sectors. They work to promote healthy coping and recovery after trauma, displacement or loss of livelihood as well as directly provide support and interventions to respond to the social impacts of emergencies. As shown during COVID-19, and summarized in our State of the Social Service Workforce Report, these impacts can be wide ranging, including escalating family poverty, violence against children, neglect and abuse of children and other vulnerable individuals, gender-based violence, child labour and child marriage.

Social service workers not only help individuals, families and communities to recover from crises and disasters, they also help them build their resilience to withstand future shocks, building on their strengths and resources to prepare and adapt so as to reduce their risk of exposure and the potential impact of future adverse events.

So, this year, for Social Service Workforce Week, in the light of the COVID-19 pandemic, and growing awareness of the wide-ranging impacts of climate change, we are seeking to recognize and advocate for the essential role of the social service workforce in disaster and emergency preparedness and response.

We invite you to join us in this weeklong campaign. On day 2, we will be examining the role of social service workers within disaster and emergency preparedness, particularly in developing resilience and capacity to cope with future crises. On day 3, we will look at the role of community level social service workers, and volunteers in particular, in humanitarian contexts. On day 4, we will hear about the vital role social service workers have played in responding and adapting to COVID-19 and what can be learned for future emergencies. Finally, on day 5 we will share examples of how the workforce can play a critical role in helping communities mitigate the impacts of climate change.

Localizing volunteer support in Kyrgyzstan during the pandemic

Submitted by Alena Sherman on Wed, 09/29/2021 - 11:41am In many contexts, volunteers have been critical for continuing social service delivery throughout the pandemic. Volunteers have increasingly been engaged to match the greater number of individuals and families in need, especially when funding constraints have prevented recruitment of more paid staff. They have also been an important way of reaching the most remote or marginalized communities, when restrictions on movement have prevented professional social service workers from doing so.

In many contexts, volunteers have been critical for continuing social service delivery throughout the pandemic. Volunteers have increasingly been engaged to match the greater number of individuals and families in need, especially when funding constraints have prevented recruitment of more paid staff. They have also been an important way of reaching the most remote or marginalized communities, when restrictions on movement have prevented professional social service workers from doing so.

Babushka Adoption Foundation works to alleviate poverty and loneliness for older people in Kyrgyzstan. Their beneficiaries live alone and receive pensions of less than about $74 a month. Babushka Adoption provides in-kind support, self-help groups and home care help, as well as the opportunity for individual sponsors to “adopt” a babushka or dedushka (literally, grandmother or grandfather) by providing personal connection and financial aid.

When the government implemented a national lockdown in response to COVID-19, transportation became extremely restricted, with driving privileges limited to police and doctors. This created an immense barrier to Babushka Adoption’s work, as staff could no longer deliver services, including cash, to beneficiaries. To adapt, the organization recruited volunteers via social media and, after assessing the needs of each beneficiary, shared that information with the newly expanded network. These volunteers brought food, financial aid and medical supplies to beneficiaries within 1.5 kilometres of their location, thus creating a more localized delivery method that could work despite the transportation limitations of the lockdown.

Recognizing the impacts of the pandemic, including social isolation, particularly on older individuals living alone, Babushka Adoption also provided psychological counselling over the phone to 280 elderly people, including some who had not previously been beneficiaries of their service. The organization recruited volunteer psychologists from local universities to help meet this growing demand.

Babushka Adoption has recognized the immense contribution of its volunteer network, including local students, and has systematized its process of working with volunteers to make it more sustainable. They developed a new written code outlining the responsibility of all volunteers, as well as the organization’s responsibilities to them, including training and transportation support outside of working hours. By formalizing the code in this way, Babushka Adoption hopes to create deeper ties to its volunteers to maintain relationships beyond the current crisis, provide guidance for their work and create a lasting volunteer system that can be used not only in the event of a future crisis, but to make the organization’s day-to-day work on behalf of elderly people more effective.

This case study and others can be found in our State of the Social Service Workforce Report 2020: Responding, Adapting and Innovating During COVID-19, and Beyond. Learn more about the role of volunteers during the pandemic and see how other organizations have adapted their service delivery.

Participants from Across the Globe Take Part in Global Conversation Event

Submitted by Alena Sherman on Thu, 09/23/2021 - 2:04pmOn 15th September 2021, the Global Social Service Workforce Alliance and Children and Families Across Borders co-hosted The social service workforce in and beyond the pandemic: A global conversation on adaptation, innovation and the fight for social justice.

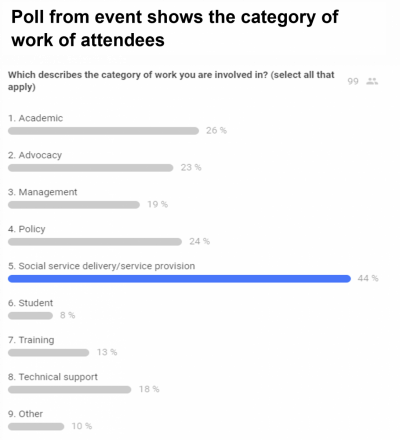

Over 260 participants from across the globe joined the virtual event to discuss the biggest issues facing the social service workforce. Participants stemmed from a broad range of roles and experiences—including social service practitioners, academics, students, policy makers and advocates—and had the unique opportunity to come together to discuss experiences and insights related to the impact of the pandemic on social service practice, education and training as well as on the role of the social service workforce in social justice.

Over 260 participants from across the globe joined the virtual event to discuss the biggest issues facing the social service workforce. Participants stemmed from a broad range of roles and experiences—including social service practitioners, academics, students, policy makers and advocates—and had the unique opportunity to come together to discuss experiences and insights related to the impact of the pandemic on social service practice, education and training as well as on the role of the social service workforce in social justice.

The event kicked off with opening remarks from Dr. Kathryn Wehrmann, Global Social Service Workforce Alliance Steering Committee Chair, followed by an overview of lessons learned from the Alliance's State of the Social Service Workforce Report 2020 by Global Social Service Workforce Alliance Director, Hugh Salmon. The event continued with three sessions, during which were placed into randomly assigned breakout rooms to discuss their experiences and insights with other participants from across the globe. Participants engaged in further discussion with one another by placing their key insights from their session into an interactive discussion platform, called Slido.

Session 1: Social service workforce practice in and beyond the pandemic

Dr. Heather Modlin, CEO with Amal Youth and Family Centre facilitated the first session on social service workforce practice in and beyond the pandemic. Breakout room conversations varied widely but key themes that emerged were around resilience and innovation. Dr. Modlin noted, "one of the things that stuck out from the breakout rooms were comments around having to go to work when half of your colleagues were sick with COVID.” She also highlighted comments from the breakout rooms around the difficulty of engaging and showing empathy while wearing a mask and shield everyday.

Other comments that emerged from the Slido forum included:

- “In South Africa we had challenges with students and community members not having equal access to internet or devices. So the digital divide was highlighted.”

- “[Personal protetive equipment] presented several problems - not only wearing it for long periods, but also creating barriers affecting non-verbal communication and difficulties for those with hearing impairments.”

- “[Social workers] not prioritized for vaccination.”

- “Ethical use of technology is also a very important aspect that was highlighted in [South Africa]. So our Council for Service Professions had guidelines published during Covid-19 for ethical use of technology.”

Session 2: Social service workforce education and training in and beyond the pandemic

Dr. Prospera Tedam, Professor at United Arab Emirates University, facilitated the second session on social service workforce education and training in and beyond the pandemic. Prospera noted, “one of the key things in the breakout rooms was that there was significant concern about whether practitioners feel ready, able and prepared…after taking a series of online placements.” She also mentioned that she heard concerns about the availability of the internet being equitable across populations as well as concerns about students being able to finance their education in these unprecedented circumstances.

Other comments that emerged from the Slido forum included:

- “I'm concerned for upcoming social workers and if they will feel as prepared after a 2 year graduate program in social work if they never really had field experience... I'm wondering how schools are actually managing this to prepare the new cohorts of social workers?”

- “I fear that for some, the inability to secure social work education placements has had major financial repercussions – I heard from a fellow student that having to extend their studies has meant they have to pay additional semesters' tuition.”

- “The virtual education methods in Colombia have not been effective, they do not recognise the social, cultural and economic context of girls, boys, adolescents and young people, thus increasing the levels of school dropout.”

Session 3: Role of the social service workforce in advancing social justice

Dr. Vishanthie Sewpaul, Emeritus Professor at the University of KwaZulu Natal, South Africa, facilitated the third session on the role of social service workforce in advancing social justice. She noted that during the breakout room discussions she heard themes around the importance of dealing with the root causes of social injustices as well as the importance of empowerment. She further highlighted comments from participants around the exacerbation of the digital divide during the pandemic and how that intensified social injustice, specifically noting that often more vulnerable populations without social protection were stuck in their choices to stay at home and risk starvation or go out and have the possibility of getting COVID-19.

Other comments that emerged from the Slido forum included:

- “Social work intervention methods, especially group work and community development can play important role in starting social justice initiatives.”

- “Understanding our own biases could be an important first step to a deeper understanding of entrenched injustices, discrimination at the societal level. How much does social work education/professional development of social service practitioners focus on helping identify our own biases, beliefs?”

- “Individuals create structures and systems that perpetuate discrimination and injustice that cause poverty, etc... social workers work with people, but typically those impacted by that injustice. How can we work more with those individuals causing the injustice?”

Missed the event? View the event recordings and PowerPoint presentations.

Developing a framework for a strengthened child protection workforce in India

Submitted by Alena Sherman on Thu, 07/15/2021 - 10:09am Issues of violence, abuse and exploitation—including domestic violence, child marriage, child trafficking, sexual and gender-based violence, child labour, corporal punishment, peer to peer violence, online abuse and mental distress—continue to plague millions of children in India. COVID-19 has further exacerbated such issues, as thousands of children have lost either one or both parents to the virus and the environments in which children grow and develop have been disrupted, increasing their vulnerability and making the effective delivery of child protection services even more critical. Yet, India continues to lack adequate human resource capacity to effectively ensure that children and their families receive quality age sensitive and gender responsive services critical for effectively responding to and preventing issues of violence, abuse and exploitation against/of children.

Issues of violence, abuse and exploitation—including domestic violence, child marriage, child trafficking, sexual and gender-based violence, child labour, corporal punishment, peer to peer violence, online abuse and mental distress—continue to plague millions of children in India. COVID-19 has further exacerbated such issues, as thousands of children have lost either one or both parents to the virus and the environments in which children grow and develop have been disrupted, increasing their vulnerability and making the effective delivery of child protection services even more critical. Yet, India continues to lack adequate human resource capacity to effectively ensure that children and their families receive quality age sensitive and gender responsive services critical for effectively responding to and preventing issues of violence, abuse and exploitation against/of children.

“The child protection workforce is not new to India, but traditionally it has been perceived as a charitable work where helping poor and vulnerable is considered to be a good karma and which does not need any training. To deliver child protection services, there is a need for a professionally trained workforce with required skills and competencies which involves paid work, this concept is still evolving, and it is relatively new,” explains Sunil Jha, National Coordinator for the Child Protection Workforce Mapping and Capacity Gap Assessment Project being implemented by the Global Social Service Workforce Alliance with support from UNICEF India.

The project aims to map the existing workforce delivering child protection services to suggest concrete measures to enhance their capacity by identifying the gaps and challenges. “One of the foremost challenges is that the proportion of workers hired is quite low compared to the magnitude and scale of the problem which our children face.” Jha continues, “…children and families need long term intervention, consistent personnel support, and a trained workforce.”

In addition to challenges in ensuring a consistent, well-trained workforce, India also faces issues related to a lack of uniformity across states in defining the criteria for appointing a social worker or member of a child protection workforce, inadequate regulation of training institutions and high staff turnover. The high turnover of staff results from the low level of pay and lack of job security, combined with the high risk inherent in the role. Risks include child protection workers facing violence or even death threats when attempting to intervene in issues of human trafficking, child marriage, child labour and domestic abuse. The workforce is often unprotected and poorly supported by the system to face such risks and endure the associated stress.

To address such issues and strengthen the capacity and resilience of the workforce to better protect children, UNICEF India has engaged the Global Social Service Workforce Alliance to map and assess the human resource capacity of the child protection workforce in five states in India—Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand, Assam and West Bengal. The mapping and gap assessment will determine 1) the number of workers in child protection positions in each district as well as their specific qualifications and experience levels, 2) gaps that exist due to human resource concerns, such as salaries, benefits and protection concerns, and 3) gaps that exist in terms of staff competencies, skills and capacity.

Working in conjunction with a Technical Advisory Group at the national level and State Steering Committees at the state level, with representation from the national and state governments, law enforcement officers, staff of one stop centers, members of civil society organizations and others, the results will be used to build consensus on the strengths and weaknesses of the workforce and priorities upon which to act. This will then translate into an agreed upon framework for strengthening the workforce, with special emphasis on case management, along with training modules on case management for key child protection actors.

While capacity assessments have been undertaken in India in the past, they have historically evaluated child protection systems from the perspective of laws, finances and processes, without taking the human resource component into account.

“This is something new. This is the first time we’re looking at human resources,” Jha explains. “[Previously] we have not assessed social service professionals, who are the important link between provision and the child. We have not assessed the workers’ capacity extensively, specifically around challenges, risks and the benefits and remunerations that they receive in return. We have not asked about motivational factors and the reasons for lack of motivation. So far, we have left [social service professionals] out from the child protection framework which, more often than not, is oriented to address specific issues, rather than to build an entire system that can protect any child at risk or in need. This is the first time we are directly consulting the child protection workforce, and hearing their voices and experiences will be critical to ultimately helping children.”

The project was delayed initially as COVID-19 interventions took priority, but Jha and his team are now in the process of developing assessment/mapping tools starting with an online survey covering all 250 districts across the five states. This will help deepen understanding of the workforce and how it could be strengthened. COVID-19 has worsened issues around child protection and placed a great burden on the child protection workforce, as they have dealt with increased safety concerns and increased caseloads.

Jha emphasizes, “It is now more important than ever that the issues facing the child protection workforce are recognized. Their views need to be heard and considered if we really want to bring about lasting change in the lives of children.”

The team will roll out the mapping and assessment in the coming months as the first steps towards developing a framework for a more strengthened child protection workforce in India.

Stay tuned for more updates as this work advances and results are received.

Barefoot Social Workers Reach Remote Areas of China with Child Protection Services

Submitted by Grace wong on Mon, 04/05/2021 - 9:41amby Save the Children China Country Office

Save the Children China Country Office offers special thanks for contributions and support from: Wenhui and his colleagues, Cangyuan County Civil Affairs Bureau, Cangyuan Women’s Federation, Danjia Township in Cangyuan and Yongwu village in Danjia Towship

Wei Wenhui is the first barefoot social worker for Save the Children's child protection project in China. He is known in the Cangyuan Wa Autonomous County in Lincang City, situated within the Yunnan Province, for the unique way he connects with the community members.

The story of Wenhui and Save the Children began in 2014. The project started as a pilot project in a neighboring township in partnership with the local village committee and the township government. On the recommendation of the village committee, Wenhui became the first child protection barefoot social worker in Cangyuan County. As social work is a relatively new but increasingly recognized profession within China, there is a growing need for community-level workers.

The title of barefoot social worker is similar to a community-level para professional worker who conducts home visits within remote communities. The title of barefoot doctor is already known within the community for health-related para professional support.

This community is near the border of Myanmar and so remote that it is not easily accessed to those who don’t live in the immediate area. The social service workforce is under-developed in this province, compared to elsewhere in China, because of its remoteness and scarcity of resources. Child trafficking, children without adult supervision and children left behind when their parents move to larger cities for jobs have created many child protection concerns. Save the Children saw a need for creating a program to recruit and train people living within the immediate community, to make access to child protection services easier as well as ensure trust of the community.

In order to promote key messages on child protection in the local area and overcome language barriers, Wenhei created songs and organized dance and drama performances about child protection in both Mandarin Chinese and the local language of Wa. This is because when Save the Children visited the villages within Cangyuan County, the children would naturally sing many different songs as a way to learn and express emotions. Children could easily recall these songs’ messages to know their rights and how to participate in their own protection. Wenhui shared that when he first started this job, the difficulties far exceeded his expectations. The parents were reluctant to provide information when he went to the house to understand the situation of the case. "At that time, no one understood what the child protection was going to do? Everyone would only think that it was their own family affair." Wenhui was often turned away.

This method is working to build the trust of the community and also children. He said, "I share my personal experiences and anecdotes with the children. On weekdays, I will organize various activities and evening shows. This is a way for me to have more contact and build natural connections with the children.”

In the summer of 2016, Wei Wenhui planned a three-day event related to the theme of child protection. It included a story exchange for the children and learning activities and lectures for community members. It was well-attended and well-received by the villagers. "It was at this time that I realized the significance of this job-I have helped many parents and children.”

The concept of protecting children and ending violence is becoming more understood and common practice within the village and Cangyuan County. Many families previously used beatings as punishment but more parents are now using the effective parenting approaches Wei has taught them.

Wenhui’s sense of mission has also brought changes to his own life. “As a child protection worker, I hope that I can take the lead and be a role model for other parents. I will communicate with my 6-year-old daughter by using some of the parenting approaches I have taught others.”

His daily work also includes training and supervising the child protection liaisons of various village groups. He supports them in knowing what information needs to be collected and how to effectively communicate with children and their families. They conduct home visits to families on a regular basis to understand the needs of children and the status of child protection. They provide support and assistance to children and families in special difficulties in the village. After the home visit, he holds meetings with the child protection liaisons or village heads to discuss the issues identified and how to follow up.

His daily work also includes training and supervising the child protection liaisons of various village groups. He supports them in knowing what information needs to be collected and how to effectively communicate with children and their families. They conduct home visits to families on a regular basis to understand the needs of children and the status of child protection. They provide support and assistance to children and families in special difficulties in the village. After the home visit, he holds meetings with the child protection liaisons or village heads to discuss the issues identified and how to follow up.

Wenhui said: "I like my job very much and I am very happy to make a contribution to child protection. I am the first person in the county to do this job. I think my work has saved many children."

Due to the success of the program, it continues to grow. There are now five barefoot social workers in the county, and the program offers a career ladder for those involved. As more resources on case management supervision are being mobilized, quality assurance measures continue to increase. And most importantly, the results are visible in the local community as more children and families benefit from increased child protection services and decreased violence.

Advocacy and innovation in social service provision in Eastern and Southern Africa

Submitted by Anonymous (not verified) on Tue, 03/16/2021 - 10:24amAdvocacy and innovation in social service provision in Eastern and Southern Africa -

‘I am because we are’ - Strengthening social solidarity and global connectedness

*reposted with permission from UNICEF Eastern and Southern Africa

By Mohamed M. Malick Fall

Today, as we mark World Social Work Day, we celebrate the important impacts of social service workers on the lives of individuals, families and communities. This year’s theme of World Social Work Day is Ubuntu: ‘I am because we are’ – Strengthening Social Solidarity and Global Connectedness. The sentiment of Ubuntu, originating in South Africa, is one that resonates regionally.

Since the onset of the pandemic, containment measures have led to increased threats to children and women’s safety and well-being including gender-based violence, exploitation, abuse, neglect, and social exclusion. Children have been confined to their homes due to school closures and hidden from public sight. Stay-at-home orders and social distancing have cut children off from the support systems they need, especially when in distress, including school, extended family, community and social services. In this context, we rely on social service workers more than ever.

Despite significant challenges during COVID-19, social service workers for child protection have swiftly adapted how they provide essential services to ensure continuity of quality care. They have committed to maintaining social solidarity and connectedness in the communities where they work during this challenging time.

UNICEF, together with the Global Social Service Workforce Alliance, the International Federation of Social Workers, the Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action, and national associations and other groups, has supported efforts to strengthen the social service workforce for child protection. We have collectively advocated to governments, policy makers and other groups in Eastern and Southern Africa to ensure these workers are considered essential service providers during COVID-19, so they can be allowed to continue their work. To assess vulnerability, identify risks, carry out case management and deliver preventative services to protect all children, these workers frequently need to be able to conduct home and school visits.

In response to an August 2020 survey, 94 per cent of countries in Eastern and Southern Africa indicated that their countries had deemed social service workers as essential service providers, enabling them to continue in-person service delivery when necessary. Some examples of these in-person services included child protection, gender-based violence, mental health and psychosocial support, family re-integration or other home visiting programmes as part of case management and assessment for at-risk or highly vulnerable circumstances.

In Malawi, the National Association of Social Workers and UNICEF worked closely with the Ministry of Population Planning and Social Welfare, related ministries and partner organizations to ensure continuity of social services to vulnerable population groups. In Lesotho among many others in the region, social workers, probation officers and community development officers were among the workers deemed essential. The South African government showed remarkable readiness for social workers, child youth care workers and other social service professionals that were assigned as essential workers under the disaster management legal framework prior to the pandemic. The Council for Social Service Professions with support from UNICEF ensured they were immediately operational and equipped with necessary skills including psychosocial support. Successful advocacy efforts by UNICEF Uganda, the National Association of Social Workers in Uganda and other partners resulted in the reopening of the national Child Helpline and official recognition of social service workers as essential in the early days of the pandemic. As a result, these workers will be prioritized as the COVID-19 vaccine is rolled out in Uganda.

The COVID-19 pandemic has also highlighted gaps in social service provision in countries all around the world. In many countries throughout Eastern and Southern Africa, the social service workforce already faced budget and staffing constraints that were stretched even further with increasing reports of child protection risks, family separation, gender-based violence, and mental health and psychosocial support needs.

With the support of UNICEF at all levels, progress was made at national and regional level to recognize the essential role of the social service workforce. UNICEF stepped in to assist in service continuity and adaptation of tools to support the workforce in meeting both existing and emerging community needs.

In some countries, this support and advocacy enabled additional funding for hiring more workers, training volunteers or task-shifting workers’ responsibilities to ensure continuity of social services.

For example, in Kenya, with UNICEF support, more than 450 child protection workers from all 47 counties were trained on various topics related to child protection with a lens of COVID-19. The 12 series of webinars provided knowledge on emerging child protection risks and skills required to provide protection and case management services remotely.

The UNICEF Ethiopia Country Office, working with the Ministry of Women, Children and Youth, facilitated the review of the National Case Management Framework tools in response to COVID-19, adding remote case management and remote child protection services provision. Additionally, the Ministry, with financial and technical support from UNICEF, has been facilitating on-the-job training of more than 1,400 ministry officials and deployment of an additional 1,226 social service workers. These workers have been deployed to support case management including family tracing and reunification of returning migrant children and to facilitate COVID-19 prevention messages and the dissemination of mental health and psychosocial support messages at community level.

The Social Workers’ Association of Zambia worked in partnership with UNICEF and the government Ministry of Community Development and Social Welfare to implement a community-based case management system that relies on para-social work volunteers and was implemented across 17 districts. A packet of minimum standards was developed with UNICEF and the Ministry is assisting NGOs to implement them as they support community-based case management systems in the districts in which they operate.

Also in Zambia, UNICEF provided support to the Ministry to establish real-time data management platforms for remote case management for children living in alternative care and children in households affected by multiple vulnerabilities. UNICEF also supported the national Child Helpline to recruit 17 additional phone counsellors to provide psychosocial support to children, including those in a refugee settlement.

In Somalia, a UNICEF survey conducted in July of child protection partners suggested that many children were not following physical distancing rules, there had been a rise in child protection violations and gender-based violence incidents, and the economic consequences of the lockdown were causing increased stress, anxiety and compounding high levels of vulnerability. Partners also reported a decreased ability to implement and monitor critical services and programmes. To respond to these new challenges, UNICEF supported the rapid training and deployment of 235 student social workers for a three-month period to work within government, district and civil society structures to provide a range of services to vulnerable women and children. These students have two-year bachelor-level social work training and received a short, one-week training on activities they were to undertake during their secondment period, to supplement the two years of bachelor-level work they had completed.

In Somalia, a UNICEF survey conducted in July of child protection partners suggested that many children were not following physical distancing rules, there had been a rise in child protection violations and gender-based violence incidents, and the economic consequences of the lockdown were causing increased stress, anxiety and compounding high levels of vulnerability. Partners also reported a decreased ability to implement and monitor critical services and programmes. To respond to these new challenges, UNICEF supported the rapid training and deployment of 235 student social workers for a three-month period to work within government, district and civil society structures to provide a range of services to vulnerable women and children. These students have two-year bachelor-level social work training and received a short, one-week training on activities they were to undertake during their secondment period, to supplement the two years of bachelor-level work they had completed.

In Eswatini, UNICEF supported the training of 70 social workers on child protection during COVID-19; the adaptation of response protocols; and the strengthening of child-related data. UNICEF also procured and distributed 70 tablets for social workers to strengthen social services during the pandemic. These were used to support the continuity of services, virtual trainings on case management during COVID-19, rapid assessments, and the broader social work mandate.

UNICEF supported the Department of Social Welfare in Eswatini to train and place 40 social work interns in quarantine facilities and to deploy additional case management officers to support district social welfare offices. Workers were provided with mobile data and voice bundles to ensure continuity of remote services. An awareness package was developed on the adaptation of Eswatini case management protocols during COVID-19.

In Malawi, police and social welfare officers have been at the forefront of handling gender- based violence, which has increased during the pandemic. Through increased collaboration, they have been providing a range of services and interventions to support those affected.

A number of countries in the region, including Kenya, Malawi, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia have begun drafting legislation to recognize social work as a profession.

Our early advocacy efforts are now also resulting in this workforce being prioritized in many countries to receive a vaccine when they arrive in the region through COVAX. The COVAX Facility’s role is to continually watch the development of COVID-19 vaccines to identify the most suitable vaccine candidates. In Angola, Botswana, Ethiopia, Malawi, Namibia, South Africa, Uganda and Zambia they are being considered essential workers to receive the vaccination either alongside or immediately following frontline health workers. In doing so, governments are recognizing the essential role of these workers while helping to keep them and the individuals and communities they serve safe.

What we have learned from COVID-19 and prior health emergencies is that we cannot wait for the next epidemic to plan, develop and support the social service workforce. Increases in gender-based violence, children’s rights violations and mental health needs, among so many other social justice and equity issues resulting from COVID-19, will not go away on their own. We need the right numbers of workers with the right training in the right place at the right time to protect children, families and communities.

On World Social Work Day, we urgently call on all governments and partners to act now to strengthen this workforce to be best positioned and prepared both to tackle today’s needs and to mitigate future emergencies.

Transitioning Colombia’s National Positive Parenting Program, Mi Familia, to Virtual Delivery During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Submitted by Juan Barco on Thu, 03/11/2021 - 9:42amSubmitted by Juan S. Barco, HRH2030 Colombia Project Director, Chemonics International; Juan P. Angulo, Technical Director, ICBF Families and Communities Directorate; Kattya De Oro, Deputy Technical Director, ICBF Family and Community Directorate; Sonia Moreno, HRH2030 Colombia Social Services Specialist, Chemonics International; Kelley Bunkers, Senior Associate, Maestral International; Sian Long, Senior Associate, Maestral International[1]

In Colombia, four out of every 10 children under the age of 18 have experienced some form of physical, sexual and/or emotional abuse in their childhood.[2] Colombia’s National Development Plan 2018-2022 states the importance of designing services to strengthen parental relationships, promote child development and decrease violence against children, calling for the promotion of family-based care. It prioritizes families with children and adolescents already in the protection system, to reduce secondary separation rates and increase successful family reunification processes.

In Colombia, four out of every 10 children under the age of 18 have experienced some form of physical, sexual and/or emotional abuse in their childhood.[2] Colombia’s National Development Plan 2018-2022 states the importance of designing services to strengthen parental relationships, promote child development and decrease violence against children, calling for the promotion of family-based care. It prioritizes families with children and adolescents already in the protection system, to reduce secondary separation rates and increase successful family reunification processes.

The Colombian Family Welfare Institute (ICBF) is the country’s main entity responsible for strengthening services for children, adolescents and families. In 2019, ICBF’s Families and Communities Directorate (FCD), the department charged with overseeing programs and services targeting vulnerable families, with support from USAID’s Human Resources for Health (HRH2030) program and Maestral International, designed a comprehensive parenting program called Mi Familia. The program is apsychosocial-based family support program that seeks to strengthen parents’ and caregivers’ ability to parent in positive, developmentally appropriate ways with the end goal of preventing violence and unnecessary separation. Mi Familia is a home-visiting program in which trained Family Support Professionals (or PAFs as per the Spanish acronym) conduct weekly home visits over 9 or 13 weeks, supplemented by four group sessions. Mi Familia is implemented by 40 approved agencies. The goal for 2020 was to reach 64,000 families in all regions of Colombia.

The implementation of Mi Familia began in early 2020. However, in March of 2020, ICBF had to rapidly adapt to a remote delivery method due to the national lockdown caused by COVID-19. ICBF FCD, with support from HRH2030, adapted the in-person curriculum to simple protocols that the PAFs could use to support families over the telephone. PAFs spoke with each family during 20-minute calls, three times a week. PAFs were provided with data for their phones to ensure that the additional work via phones could happen in a timely manner. Mi Familia’s operational structures remained the same, maintaining the same number of PAFs in order to ensure high quality services and personalized attention. In fact, the program’s savings in transportation costs were invested in greater technological resources.

The shift to virtual happened quickly, yet PAFs reported feeling supported and prepared to deliver the virtual model. Technical Assistance Professionals helped to review the virtual guides that were adapted from the in-person manuals. Their input was instrumental in ensuring that implementation would be feasible. There were virtual training sessions provided by the Technical Assistance Professionals, and ongoing discussion groups where PAFs could share their concerns or challenges. These were then communicated to ICBF. Most agreed that the flexibility shown by ICBF and the trust shown in the ability of PAFs to deliver content was an empowering element that contributed to overall success as was mentioned in a focus group discussion. As one PAF noted, "The Technical Assistance Professionals support us, listen to us, and that has helped us a lot to lower the stress not only of work but about ourselves as human beings."

The virtual delivery of Mi Familia formally began in May 2020. At the same time, a monitoring plan was designed to assess the virtual implementation process, using three monitoring tools. The first, a Family Satisfaction Survey, included 10 simple questions on overall levels of satisfaction with the program and specific questions related to content and delivery. ICBF’s call center staff surveyed 282 families between August and October 2020. The second tool was a more detailed questionnaire to selected PAFs regarding content and delivery, focusing on their perceptions of families’ satisfaction and engagement to the program and their successes and challenges. The third tool was a series of six focus group discussions with PAFs and technical support unit staff, focusing on qualitative aspects of the successes and challenges in the transition to virtual delivery.

Findings illustrated that ICBF FCD had transitioned from in-person to virtual delivery of Mi Familia rapidly and effectively. Both families and PAFs felt the information and topics were relevant for parenting roles and helpful for children and adolescents. Indeed, 95.6% of the families surveyed felt satisfied with the program. Additionally, 98.3% of the PAFs surveyed responded that they always or almost always achieved session objectives, and 90.6% reported that families always or almost always understood key lessons and information in the session. A total of 99% of the PAFs felt prepared to answer the family’s questions, and 96.1% of the households confirmed this by reporting that they considered the PAFs able to clarify questions. PAFs proved to be innovative and creative in how they engaged with families and delivered the program.

The research was able to identify a number of important successes, which have been incorporated into ongoing developments of Mi Familia. These include validation of the benefits of evidence-based positive parenting approaches and the recognition of a flexible approach that enabled skilled facilitators to continue to adapt the program needs to individual families.

The virtual delivery clearly illustrated that a blended implementation is possible for a positive parenting program. As such, this would allow government entities to deliver these kinds of programs to regions and populations that historically were not targeted, specifically because they were determined as being hard to reach.

The research also identified a number of important challenges that are being addressed currently in the adaptation of Mi Familia moving forward. These include three core issue: 1)the need to focus further on how to promote children’s and adolescents’ participation in the program; 2)to better understand and address the barriers to male participation; and 3)to develop a greater focus on promoting referrals to other care providers through awareness-raising with PAFs and improved coordination with other ICBF departments and external service providers.

Moving forward, Mi Familia aims to serve 280,000 families throughout the country by the end of 2022. ICBF FCD is confident that a blended model can build on the positive experiences from the virtual program. To do so, it is necessary to strengthen training and supervision, and strengthen the relationship between the PAFs and those professionals engaged in and responsible for making care decisions, such as children’s placement in alternative care or reintegration. Finding ways to strengthen these linkages will be an important step in future implementation.

This blog summarizes a presentation given by Juan S. Barco, Juan-Pablo Angulo, and Kelley Bunkers at the CORE Group’s January 2021 Conference, Unlocking Potential: Prioritizing Child & Adolescent Health in the New Decade.

Recognizing the essential role of the social service workforce for child protection - In March and everyday

Submitted by Anonymous (not verified) on Wed, 03/10/2021 - 12:00amReposted from UNICEF Eastern and Southern Africa with permission. View the original.

Throughout the month of March and on World Social Work Day on March 16, social service workers around the world are celebrated and recognized for their essential role in the daily lives of individuals, families and communities.

Throughout the month of March and on World Social Work Day on March 16, social service workers around the world are celebrated and recognized for their essential role in the daily lives of individuals, families and communities.

As we raise our voices in appreciation, now is also an opportune time to call for increased recognition and support for the crucial frontline role played by these workers during and prior to COVID-19.

The social service workforce for child protection plays a central role in promoting social justice; reducing discrimination and root causes of inequality; challenging harmful behaviours and social norms; preventing and responding to violence, abuse, neglect and exploitation; tackling harmful practices such as child marriage and female genital mutilation; and addressing family separations especially among migrants, refugees and internally displaced persons.

They also support poverty reduction initiatives, including social protection and cash transfer programs, and respond to humanitarian crisis situations.

This year’s theme of World Social Work Day is Ubuntu: ‘I am because we are’ – Strengthening Social Solidarity and Global Connectedness. Ubuntu originates from the indigenous peoples of South Africa and was popularized across the world by Nelson Mandela.

Nurturing relationships are central to social service professionals in all aspects of work. The promotion of indigenous knowledge remains critical to informing approaches to delivery of social service interventions.

As we reflect on the challenges of the past year, we also must recognize the unsung heroes who continued carrying out essential services during this time. COVID-19 has had a significant impact on how the social service workforce delivers services and interventions.

At a time when individuals and communities, as well as workers themselves, face heightened challenges, the social service workforce has remained at the heart of building connections and linkages and ensuring the continuity of promotive, preventative and responsive services.

Social service workers ensure healthy development and well-being for children, youth, adults, older persons, families and communities. During COVID-19 they have carried out many essential services.

Social service workers are essential

New safety concerns and the resulting need for technology to connect with people remotely have impacted how the social service workforce have reached the most vulnerable children and their families.

UNICEF has provided funding, technology, training and advocacy to support social service workers in being adaptive, creative and flexible in innovating new ways of making their services effective, while still upholding their professional values and standards of service.

In many communities, social service workers also provide health education and link with education, justice and health services for a continuum of care and services.

This transformation in social services has helped them transform lives under the most difficult circumstances.

In an online survey conducted by the Global Social Service Workforce Alliance in April 2020 to determine the types of services the social service workforce is providing during COVID-19, 54 per cent of respondents indicated they are providing mental health and psychosocial support services.

Mental health and psychosocial support needs have been exacerbated during this period of heightened stress.

Workers also shared that they are providing a range of child protection and gender-based violence services, ensuring children affected by COVID-19 have access to adequate alternative care arrangements and delivering protection services for children left without a care provider.

In a recent blog, Cornelius Williams, Associate Director and Global Chief of Child Protection for UNICEF Programme Division, highlighted the important role of the social service workforce for child protection and UNICEF’s continued commitment to ensuring they have the necessary tools to carry out this important work.

“The pandemic has brought social service workers who are often invisible – working “behind the scenes” – to the forefront and helped [UNICEF] highlight the critical role they play in children’s lives…Now is their time to take centre stage in this decade of action and beyond.”

As UNICEF continues to join with practitioners, organizations and other groups in celebrating the many ways this workforce has provided essential services during COVID-19, we must also act now to ensure they are properly equipped to address the many new and increased inequities individuals and communities will face long after the pandemic itself ends.

We call on all governments to invest now in this frontline workforce and develop supportive policies to ensure that the proper number of trained workers is available to meet immediate and ongoing needs. By doing so, everyone in the community will benefit.